Finding the Root Causes to Systems Challenges

This article highlights lessons learned from the 2024 workshop with Daniela Papi-Thornton, a cofounder of Map The System Global.

Linh Bui

In any complex challenge, identifying the root causes of a problem is essential to building a sustainable and impactful solution. However, as systems thinker Daniela Papi-Thornton explains, the process of finding root causes is often misunderstood as a simplistic task rather than the nuanced, context-driven exploration that it truly is. Root cause analysis is not about identifying one singular, definitive problem point but about understanding the interconnected factors that contribute to systemic issues. In this blog, we will explore tools, strategies, and mindsets necessary to uncover root causes in a meaningful way

Table of Contents

The Misconception of "One Single Root Cause"

A common pitfall in problem-solving is treating complex, systemic challenges as though they share the same characteristics as a mechanical system like a clock. Mechanical systems are finite, predictable, and their breakdowns can often be traced back to one faulty component. However, societal challenges such as homelessness, climate change, or inequity operate within dynamic systems shaped by countless interrelated factors. As Papi-Thornton emphasizes, in such systems, there is no single "correct" root cause. Instead, the value lies in the process of mapping interconnections and discovering leverage points.

For example, a well-intentioned initiative in rural Cambodia aimed at improving education by building a school revealed deeper systemic issues such as unpaid teachers and cultural factors limiting attendance. Similarly, in the context of homelessness, solving "housing shortages" might ignore deeper challenges such as mental health support, policy barriers, and systemic inequities. These examples illustrate how an oversimplified approach can lead to "solving the wrong problem."

“There likely isn’t a root cause. Usually there are LOTS of causes at LOTS of levels. This isn’t about finding the answer.” - Daniella Papi-Thornton

The Importance of Context and Lived Experience

One of the key lessons from systems mapping is that solutions often fail because they lack contextual understanding or exclude the voices of those directly impacted. In Papi-Thornton’s experience, tools like causal loop diagrams and system maps are only as effective as the participatory processes behind them. Engaging communities in co-designing solutions ensures that the diverse perspectives necessary for system-wide clarity are at the forefront.

For instance, addressing inequitable access to green spaces might mean very different things depending on one's perspective. A policymaker might emphasize zoning laws, an activist might focus on environmental racism, and a parent might simply want safe parks for their children. By integrating these varied lenses, a systems thinker can reveal connections, boundaries, and underlying dynamics guiding the problem. Essentially, understanding a problem in the context of its local, cultural, and systemic realities is critical to identifying actionable root causes.

Tools and Frameworks for Analyzing Root Causes

To clarify the complexity of systemic issues, Papi-Thornton suggests tools like process mapping, the Five Whys approach, and Danella Meadows’ "12 Leverage Points." These tools encourage structured thinking while respecting the organic, iterative nature of systems work.

The key is understanding that tools are not an end in themselves; the process of building them with the wider system's stakeholders is where learning and insight are generated.

1. The Five Whys Technique

The Five Whys Technique is an iterative method to probe the root causes of systemic social challenges by asking "Why?" repeatedly.

Steps to Apply the Five Whys in Social Research

Define the Problem: Clearly articulate the observed issue. For instance, "Why are high school dropout rates higher among minority students?"

Ask Why Iteratively: Each response becomes the basis for the next "why." Example:

Why are dropout rates high? Because many students miss school frequently.

Why do they miss school? Because they work part-time jobs to support their families.

Why must they work? Because their families face poverty.

Why are their families facing poverty? Because they lack access to well-paying jobs due to education disparities.

Why do education disparities persist? Because schools in low-income areas receive less funding and resources. More example: (1) (2).

Design Interventions: Once you identify the root cause, develop targeted actions to address it—for example, increasing school funding in underserved areas or launching family assistance programs.

Example: Homelessness

Problem: High rates of chronic homelessness in a city.

Why is homelessness so prevalent? Because of a lack of affordable housing.

Why is there a lack of affordable housing? Because of insufficient housing development for low-income families.

Why are there insufficient developments? Because city zoning laws prioritize commercial developments over residential ones.

Why are zoning laws structured this way? Because stakeholder interests skew toward economic growth instead of social welfare.

Why do these stakeholder interests dominate? Because low-income groups have limited representation in policymaking.

This analysis directs policymakers to reform zoning laws and include diverse stakeholder inputs.

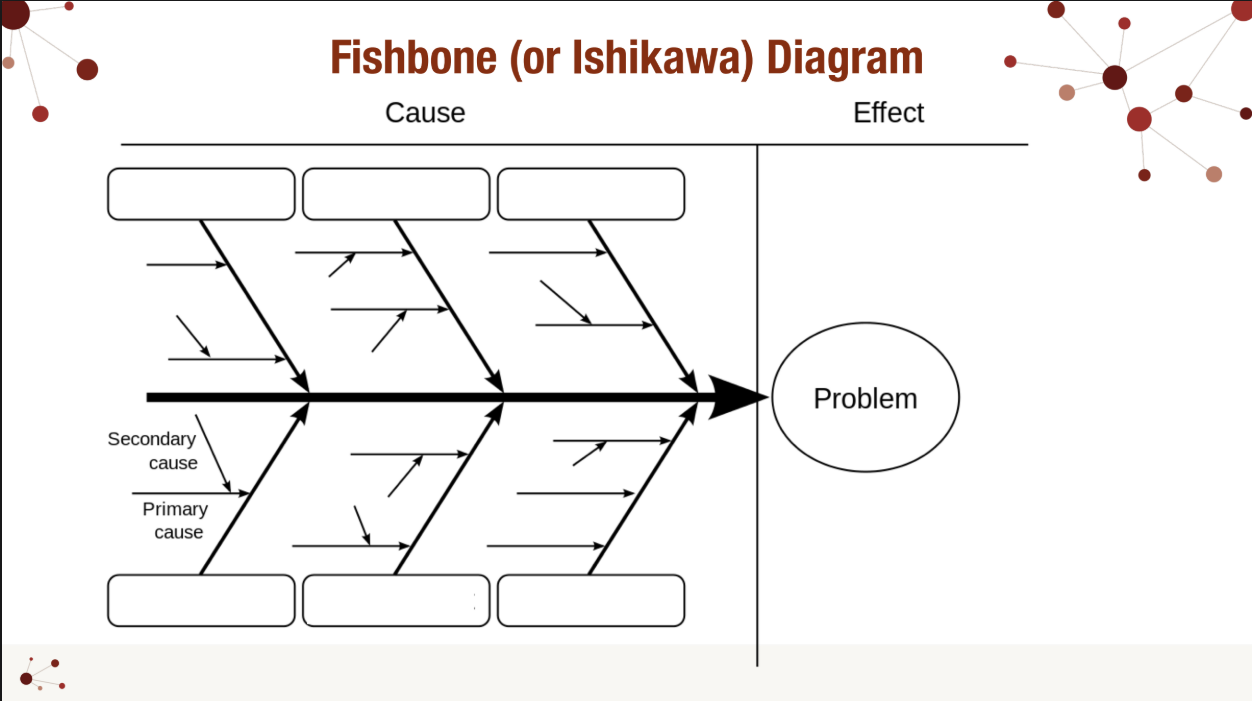

2. Ishikawa (Fishbone) Diagram

The Ishikawa Diagram visually organizes the contributors to systemic issues, progressively narrowing them down to root causes.

Steps for Creating an Ishikawa Diagram in Social Research

Refine the Problem Statement: Place the issue at the "head" of the fish. Example: "Educational disparities among marginalized communities."

Determine Main Categories of Causes: Use broad themes like “Funding,” “Access,” “Curriculum,” “Teacher Training,” and “Cultural Barriers” as "bones."

From Your Research and Interview Findings, List Specific Causes: Populate each bone with sub-causes.

Example: Systemic Racism in Criminal Justice

Problem Statement: Higher rates of incarceration among minority populations.

Main Categories (Bones):

Policing: Racial profiling, unequal enforcement of minor offenses.

Judiciary: Bias in sentencing guidelines, underrepresentation in jury selection.

Economic Inequities: Lack of access to quality legal defense, bail system disparities.

Historical Context: The legacy of discriminatory policies like redlining.

Sub-Causes: Under “Economic Inequities,” courts disproportionately penalize those unable to afford bail. More example: (3) (4).

This highlights systemic weak points and informs reforms like eliminating cash bail systems or implementing anti-bias training for law enforcement.

For more examples, read Root Cause Analysis Resources.

3. Donella Meadows' 12 Leverage Points

Meadows' framework identifies specific systemic entry points for high-impact interventions, ordered by effectiveness.

Key Leverage Points (In Order of Effectiveness)

Paradigms: The mindset or overarching belief system from which the system is built (e.g., shifting from growth-focused to sustainability-focused objectives).

Goals of the System: What the system is designed to achieve (e.g., redefining success metrics from profitability to community impact).

Structure of Information Flows: Who has access to data and how decisions are communicated?

Rules of the System: Incentives, penalties, and constraints guiding behavior.

Delays: Reducing lag time between actions and outcomes.

Material Stocks and Flows: Managing physical or informational resources.

Feedback Loops: Strengthening negative (stabilizing) feedback or amplifying positive (growth-oriented) feedback.

Example:

Paradigms (Deepest Root Cause Level)

Root Cause Identification: If gender inequality persists despite policy changes, the underlying cause might be societal beliefs that devalue women’s contributions.

Example: The belief that women’s income is “supplementary” to household earnings leads to wage gaps and workplace discrimination.System Goals

Root Cause Identification: If schools fail to address educational inequities, the problem may stem from what they prioritize.

Example: Schools prioritize standardized test scores, which disadvantages students from under-resourced communities rather than focusing on equitable learning environments.Rules

Root Cause Identification: If there’s a housing crisis, the issue may not be a lack of houses but restrictive zoning laws.

Example: Regulations prevent affordable housing developments in high-income areas, reinforcing segregation and economic inequality.Structures & Feedback Loops

Root Cause Identification: If women’s entrepreneurship is low, it may not be due to a lack of skills but a lack of financial access.

Example: Banks deny women loans at higher rates, preventing business growth and reinforcing economic dependency.

Combining Five Whys, Ishikawa, and Leverage Points

When used together, these tools ensure multi-faceted problems and gaps.

Example: Environmental Health Disparities

Start with Five Whys:

Problem: Disproportionately high asthma rates in underserved urban areas.

Why? Poor air quality near residential neighborhoods.

Why? Proximity to industrial facilities.

Why? Lack of zoning restrictions separating industrial and residential areas.

Why? Historical advocacy gaps in these communities.

Why? Systemic disempowerment of marginalized groups.

Visualize with an Ishikawa Diagram:

Key Categories: Urban Planning, Legislation, Community Awareness, Health Systems.

Sub-Causes: Inadequate health interventions under “Health Systems” or non-compliance with emissions standards under “Legislation” (Source).

Intervene Using Leverage Points:

Change Paradigm: Promote the viewpoint that "clean air is a fundamental right."

Shift System Rules: Push for emission standards and urban waste zoning diversification. Improve Information Flows: Develop public alert systems on air quality risks.

The Value of Reframing Problem Before Identifying Root Causes and Gaps

Root causes often reveal themselves when we reframe the problem. Reframing requires stepping back from assumptions of what the solution "must" be, as assumptions often narrow our scope prematurely. For example, instead of framing a school attendance problem as “lack of infrastructure,” reframing might reveal underlying systemic barriers like cultural attitudes toward education or economic constraints requiring children to farm rather than study.

Papi-Thornton also discusses the importance of recognizing personal motivations in this process. Teams must ask themselves, "Why do I care about this issue?" and evaluate whether their interventions align with both their values and the root causes they wish to address. This self-awareness reduces the risk of imposing top-down solutions disconnected from community realities.

Odin Mühlenbein, who runs Ashoka’s Globalizer program, an accelerator program for advanced social entrepreneurs…He notes, ‘50% of the work happens just in defining the title of the map: what system are your looking to map?’. He encourages people to spend time thinking about the title, which puts a boundary around the system map, before jumping into the 5Rs. (The Student Guide to Systems Thinking, p. 55).

Root cause analysis is not about finding a single problem to solve but about deepening our understanding of the systems we aim to influence. It requires abandoning linear, siloed approaches in favor of collaborative, context-sensitive inquiries. By using mapping tools, prioritizing inclusive processes, and maintaining humility, we unlock new pathways for creating meaningful change.

In our efforts to address societal challenges, we must embrace both the complexity of the systems we navigate and the insights from those directly impacted. Only then can we effectively and sustainably contribute to solving the challenges of our time.